Women in Shadows: The Female Figures in Klimt’s Paintings

Share

Gustav Klimt’s work is often celebrated for its decorative elegance, its gold leaf, and its sensuality. Yet beneath the shimmering surfaces lies a profound meditation on the complexities of female identity. The women in Klimt’s paintings are rarely passive objects of desire. They are figures suspended between visibility and obscurity, power and vulnerability, intimacy and isolation.

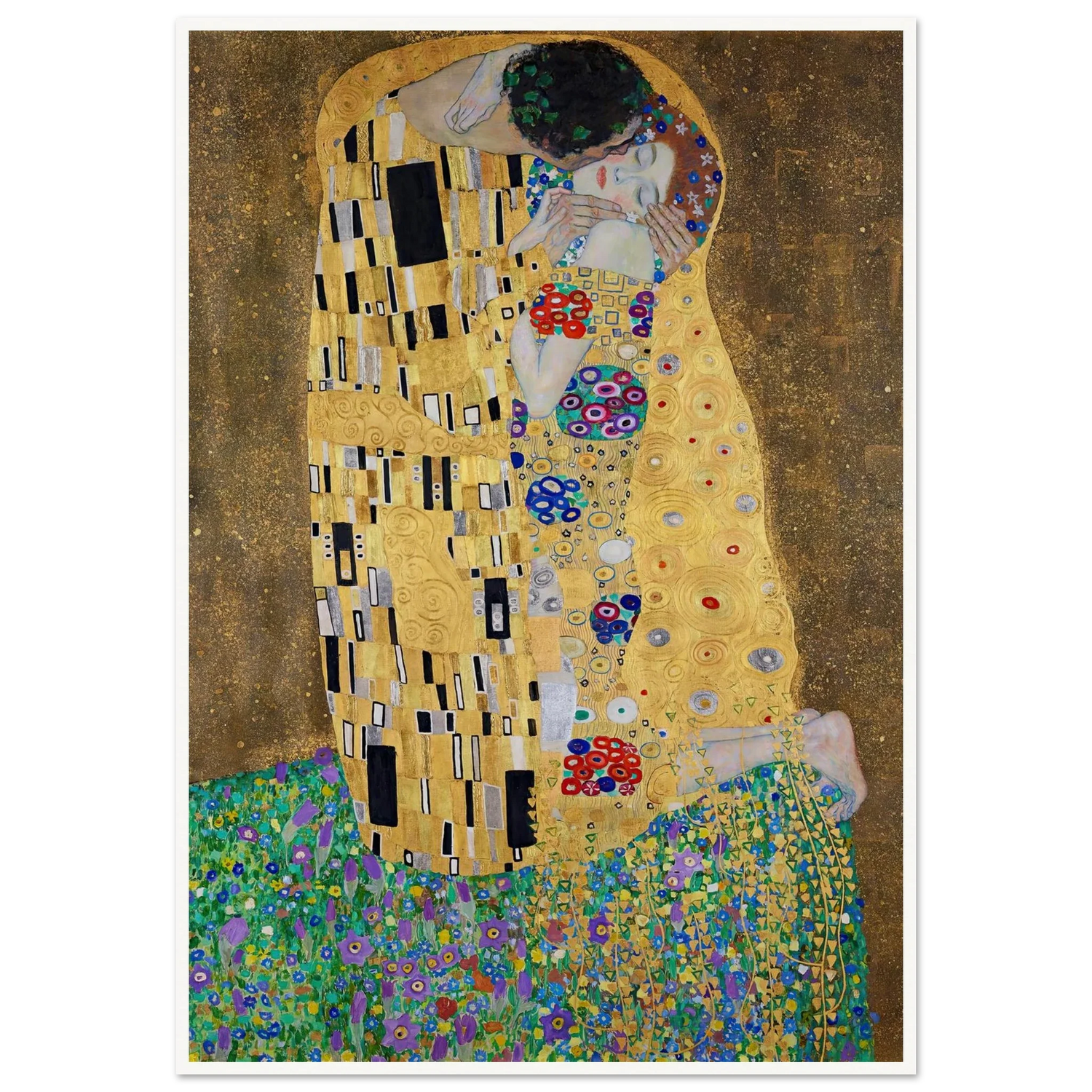

In The Kiss (1907–08), the most iconic image, the woman’s face is partially hidden, turned into the fold of her partner’s embrace. Her body is entwined with his, yet there is a sense of private thought preserved behind her closed eyes. This is not surrender. It is contemplation. Her presence asserts an inner life that cannot be fully absorbed by the viewer.

In Judith and the Head of Holofernes (1901), the female figure is commanding, terrifying, and enigmatic. Judith’s gaze is direct, sharp, and almost predatory. The gold patterns surrounding her accentuate her figure but also serve as a visual veil. Klimt’s women are rarely accessible at first glance. They exist in a space where decoration and identity intersect, making the viewer work to understand them.

The subtle shadows and layering in Klimt’s portraits emphasize psychological depth. In works such as Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907), the sitter is adorned in gold and intricate patterns. The embellishments might seem to dominate, but they also isolate her, creating a visual rhythm that both reveals and conceals. Her expression is serene yet unreachable. Klimt balances eroticism and autonomy, making each woman both a subject and a cipher.

Klimt’s treatment of women in shadow reflects more than aesthetic preference. It is a deliberate choice to explore how female identity interacts with societal expectation, desire, and visibility. These figures are powerful precisely because they are not entirely legible. Their bodies may be exposed, their faces partially hidden, their gaze evasive or commanding. The tension between what is shown and what remains secret defines Klimt’s enduring fascination with the feminine form.

Viewing these paintings, we understand that Klimt does not objectify. He engages. He sets a challenge. The female figure is at once the center of attention and a boundary to comprehension. We are invited to linger, to study, and to confront the subtleties of intimacy, power, and mystery that the shadows suggest.

In the end, Klimt’s women are mirrors of both artist and audience. They demand observation, contemplation, and respect. They are not passive symbols. They are active presences, quietly reshaping how we perceive beauty, power, and autonomy in art.